SUBTLE SENSATION

Sharing is a double-edged sword. On the downside, there are the uneasy compromises: you pay for getting half of what you want by eating half of what you don’t; then there’s the fear you might take too much or too little. The benefit is simple: you get to eat more nice things. It boils down to trust in your partner/s in crime; and an agreement that things like prawns must be counted. There is no space for shellfish behaviour or false nonchalance when it comes to sharing, but my wife and I have practised the fine art for many years, I reflected as we arrived at Le Flamant in Lindfield for lunch on a sunny July day.

CONFIDENT MENU

Le Flamant, which landed in the pretty, well-heeled town of Lindfield earlier this year, is not a restaurant that sticks to the trusty tricolore of first/main/pudding. Instead, the menu is made up of a few nibbles or a charcuterie plate to start, followed by ten ‘plates’, then a choice of two puddings or the cheese plate. Any format anxiety was instantly dispelled by the manager, Molly, who seated us and explained the rules of engagement: basically, four to five plates to share between two and, of course, the possibility of pudding, which became a certainty when we spotted deep-fried cherry pie.

For someone whose favourite restaurant has no menu at all, this short list of temptations was a delight: an expression of confidence that the chef has a firm idea of what’s good this month, and a focused idea of what we should be eating. Eliminating one or two, then deciding on the rest was painless: a little bowl of homemade pickles (the straw mushrooms were a delight) kept us entertained with a glass of light, organic falerio chosen for us by Molly; then tempura mussels with a curry tartare sauce; tomato salad in a creamy aubergine dressing topped by the finest homemade crisps you can imagine; halibut with a ajo blanco/parsley pesto sauce; and sirloin of beef in chicken sauce.

The ‘nearly-made-its’ were seared scallops and beef tartare, the former edged out by the mussels, the latter a victim of sharing culture; my wife is not the biggest fan. Nonetheless, it was reassuring to know that the English are still up to the conceptual challenge of beef tartare; it’s a staple here, undergoing endless variations on a menu that changes fortnightly, keeping chefs Jackson Heron and Felicity Mosely, and their diners, on their feet.

SOPHISTICATION AND EVOLUTION

The tempura mussels were a little moment of greatness: the idea of enveloping the meatiest of all shellfish in the world’s lightest batter is a sound one, and it was one of those dishes with a sauce so well matched that choosing whether or not to dip became an agony.

The sophistication of sauces continued as the most notable theme in every dish that followed, from the complex, subtle aubergine dressing on the tomato salad, to the incredibly deep chicken stock reduction that accompanied the (excellent) sirloin of beef.

But the one that draped itself over the halibut was really a masterclass for a saucier: mysterious, nutty and delicate in flavour and as lovely to behold as a Georgia O’Keeffe oil painting. The mystery turns out to be a combination of ajo blanco (a thick Spanish bread-and-almond sauce/soup) and parsley pesto, which sounds like salsa verde but tastes nothing like it.

Nearly everything is as original as this, but not in a way that shouts at you: it’s all a product of sober, vigorous evolution based on a firm foundation of good sense and broad knowledge. It’s very big and it’s very clever, but it’s underplayed: it’s genuinely classy; there’s no other way to put it.

BISTRO CHIC

By this point, 1pm, the dining room had nearly filled up, although the good acoustics meant that it was still easy to talk. The design of Le Flamant has been thought through; the cool, stone-coloured hessian on the walls (nothing like the coarse, yellow weave popular in the 1970s) gives the place a warm vibe and soaks up reverberation, giving good acoustic deadening, something ignored by too many restaurants. It helps that the air-conditioner is somehow completely silent too.

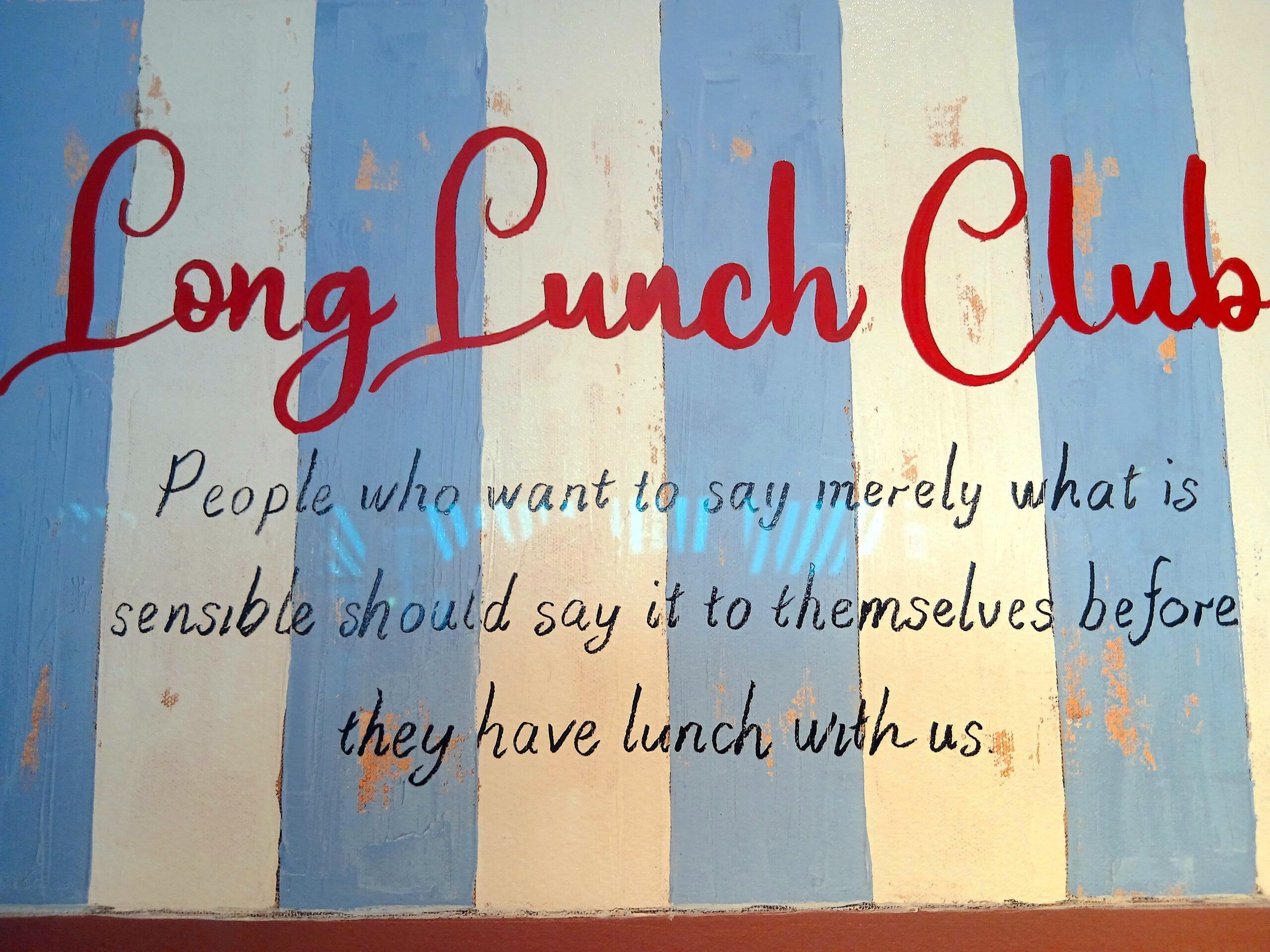

The walls are covered in photos of the south downs and colourful prints that bear a nod to the French bistro look, as do the half-height curtains at the front and the smart stripy awning and menu on a stand outside. ‘Le flamant’ is in fact French for flamingo, as hinted at by the restaurant’s logo.

DEEP FRIED CHERRY PIE

Pudding was different. There’s nothing classy about banoffee pie. It’s a favourite of both of ours, and was invented – or at least formalised from a close American relative – just 30 miles away in Jevington, East Sussex. So we played tribute, and didn’t regret it, enjoying one of the lightest versions we’ve ever tried.

The deep-fried cherry pie with vanilla chantilly appealed instantly as a concept, and for the fact that there was no “with icecream” option. Again, that confidence: if Chef says it goes with chantilly, not ice cream or custard, then why introduce the risk of diners making a false move? The pie itself was an incredibly rich, deep creation in flaky, shiny pastry and, like the banoffee pie, will absolutely not count as one of your five a day.

It’s hard to pin Le Flamant down. The plates concept is similar to tapas, but the overriding feeling is French, mixed with local sensibility: some of the wines are local and the tomatoes are from the nearby Nutbourne farm and vineyard. No one talks about ‘fusion’ cuisine any more, and what Le Flamant serves up has none of the contrivance that term implies: it’s very natural, another paragraph in the long love letter that generations of British chefs are still writing to France and beyond. You could, if forced, call it ‘modern European’, but it’s too good, and too ephemeral.

Go with someone you know who loves cooking, and try it for yourself. Just be sure they know how to share.